Working with C++ Types and Virtual Function Tables¶

Derived Classes¶

Structures in Binary Ninja can be derived from other structures, allowing C++ class hierarchies to be represented without having to redefine base class members. Defining the class hierarchy in Binary Ninja will also allow the cross references to reflect the hierarchy, such that base class members are cross referenced in all derived classes automatically.

In-memory layout of C++ classes is not defined by the standard and varies by compiler, so Binary Ninja provides a low-level representation for describing the class layout.

Defining a Derived Class or Structure¶

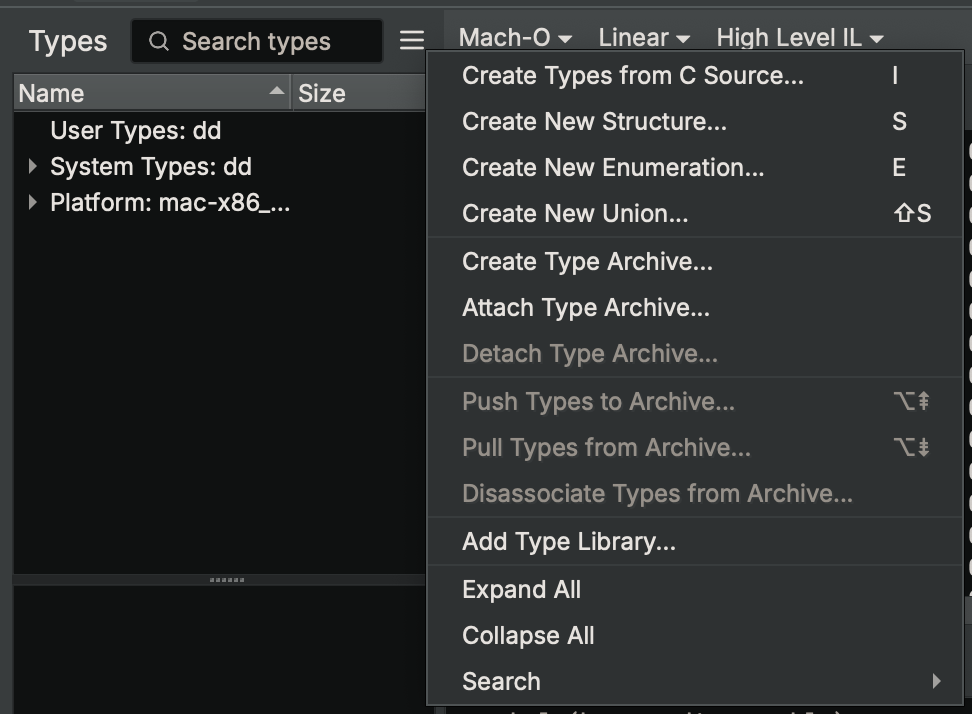

A derived class can be defined using the Create Structure dialog. From the Types sidebar this

dialog can be opened with a default hotkey of s or by using the add menu on the right of

the sidebar.

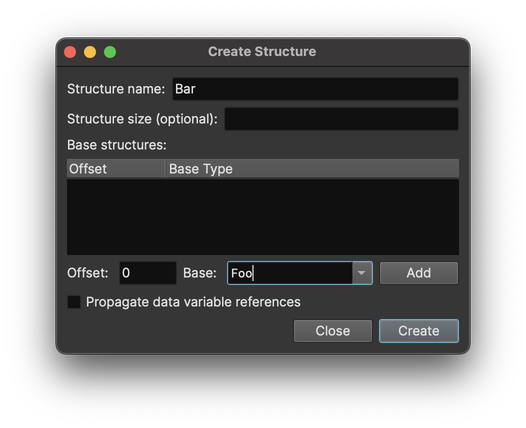

First, enter the offset and name of the base structure below the "Base structures" list. The offset should be where in the derived structure to place the base structure's members, which will usually be zero for single inheritance.

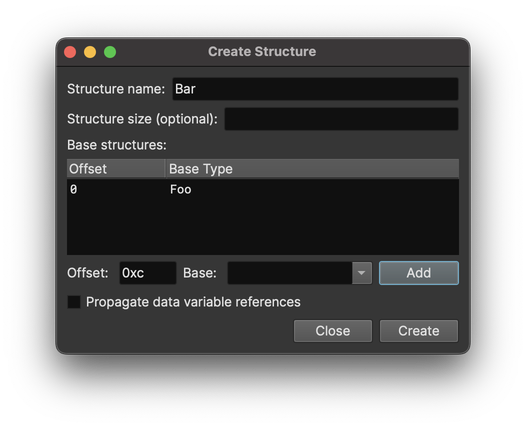

Click the add button to add the base structure to the new structure.

The offset will automatically update to be just after the added structure in case you need to add additional base structures. Click the Create button to create the new structure.

The new structure will appear in the types sidebar with special syntax to show the base structures and the inherited members:

struct __base(Foo, 0) Bar __packed

{

__inherited int32_t Foo::field_0;

__inherited int32_t Foo::field_4;

__inherited int32_t Foo::field_8;

};

This syntax can also be used in the Create Types interface to create derived structures

from C source. When creating types from the Create Types interface, __inherited members

need only match the structure's size and can be more easily defined like this:

struct __base(Foo, 0) Bar

{

__inherited Foo foo;

};

Derived structures can also be defined using the API. Use the base_structures property of

the structure builder to do this. It takes a list of BaseStructure objects, which are defined

using a Type and an offset.

s = TypeBuilder.structure()

s.base_structures = [BaseStructure(bv.types['Foo'], 0)]

Virtual Function Tables¶

Virtual functions are implemented by compilers using a virtual function table structure that is pointed to by instances of the class. The layout of these structures is compiler dependent, so when reverse engineering a C++ binary these structures must be created to match the in-memory layout used by the binary.

One of the most common tasks when reversing a C++ binary is discovering which functions a virtual function call can resolve to. Binary Ninja provides a "propagate data variable references" option in the Create Structure dialog to help with this. When this is enabled, pointers found in the data section that are part of any instance of the structure will be considered as cross references of the structure field itself. This allows you to click on the name of a virtual function and see which functions it can potentially call in the cross references view.

Defining a virtual function table¶

To create a virtual function table, select the "propagate data variable references" option when

creating the structure in the Create Structure dialog. Alternatively, use the __data_var_refs

or __vtable attributes (these are aliases of each other) when creating the structure from

C source. Here is an example virtual function table structure:

struct __data_var_refs vtable_for_Foo

{

void (* fizz)(struct Foo* this);

void (* buzz)(struct Foo* this);

};

Now, apply the new virtual function table structure to each instance of the table in the data section. You can usually find pointers to them in the constructors.

Derived virtual function tables¶

Virtual functions are typically used in conjunction with derived classes. In order to get the

best results from Binary Ninja, each class should have its own virtual function table structure,

and the virtual function table structures should use the base structures feature described

earlier to mirror the class hierarchy. For example, if the class Foo mentioned in the virtual

function table above has a derived class of Bar, you would define a second virtual function

table structure vtable_for_Bar that derives from vtable_for_Foo:

struct __base(vtable_for_Foo, 0) __data_var_refs vtable_for_Bar

{

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Foo::fizz)(struct Foo* this);

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Foo::buzz)(struct Foo* this);

void (* beep)(struct Bar* this);

};

You should always define these derived virtual function table structures, even if they have the same members. This allows Binary Ninja to get more accurate results.

The last step is to ensure that the virtual function tables are pointed to correctly in the class itself. This is often the first member of the structure. Make sure that each class points to its own virtual function table structure. Derived structure members can be overridden simply by changing their type.

The example Foo and Bar classes would look like this:

struct Foo

{

struct vtable_for_Foo* vtable;

// Foo members

};

struct __base(Foo, 0) Bar

{

struct vtable_for_Bar* vtable; // Overridden Foo::vtable

// __inherited Foo members

// Additional Bar members

};

Tip

Do not leave the vtable members deriving from the base class. You should always make a

derived virtual function table structure for each new class, and override the vtable

member to point at the corresponding structure. This will significantly improve Binary

Ninja's cross references for virtual function calls.

Template Simplifier¶

The analysis.types.templateSimplifier setting can be helpful when working with C++ symbols.

Example¶

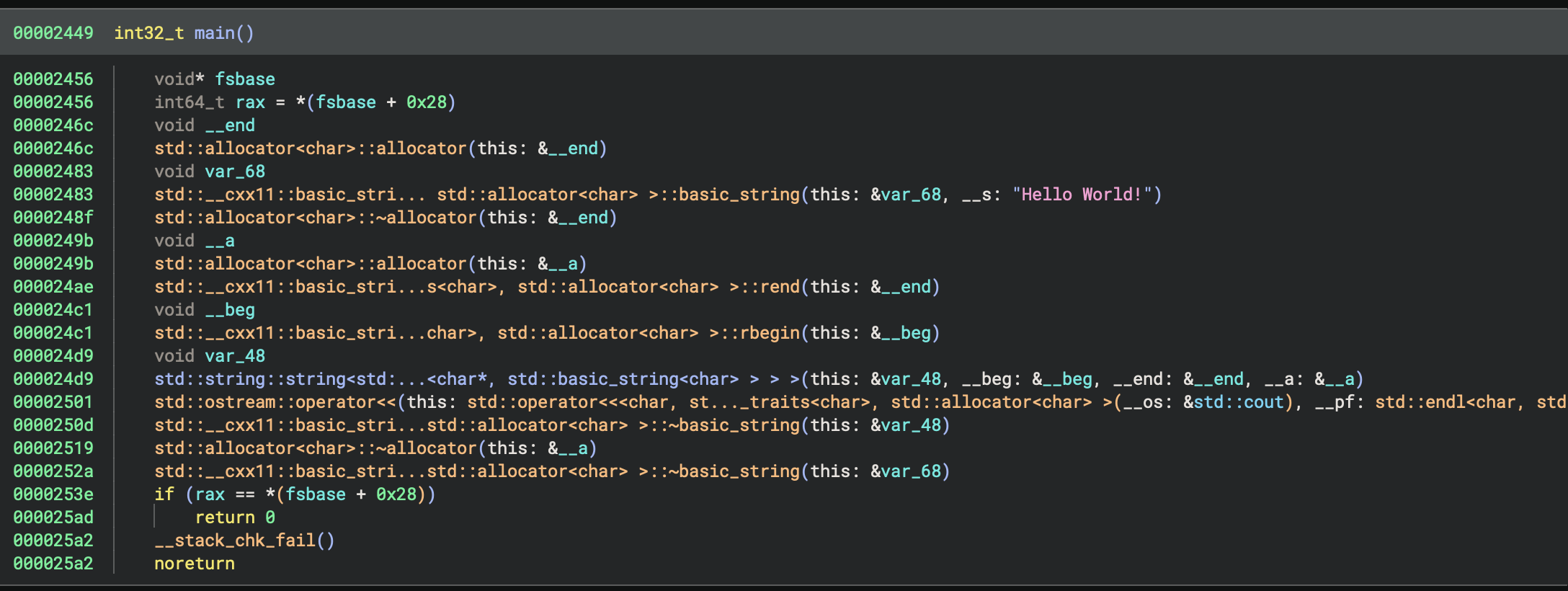

Consider the following C++ program:

class Animal

{

public:

const char* name;

virtual void make_sound() = 0;

virtual void approach()

{

make_sound();

}

void greet()

{

printf("You:\n");

printf("Hello %s!\n", name);

printf("%s:\n", name);

make_sound();

}

};

class Flying

{

public:

int max_airspeed;

virtual void fly()

{

puts("Up, up, and away!");

}

};

class Dog: public Animal

{

public:

int bark_count;

virtual void make_sound() override

{

puts("Woof!");

bark_count++;

}

};

class Cat: public Animal

{

public:

int nap_count;

virtual void make_sound() override

{

puts("Meow!");

}

virtual void approach() override

{

if (nap_count)

puts("Zzzz...");

else

make_sound();

}

virtual void nap()

{

nap_count++;

}

};

class Lion: public Cat

{

public:

virtual void make_sound() override

{

puts("Roar!");

}

};

class Bird: public Animal, public Flying

{

public:

int song_length;

virtual void make_sound() override

{

for (int i = 0; i < song_length; i++)

puts("Tweet!");

}

virtual void approach() override

{

fly();

}

};

Defining the base classes¶

First, we define the base classes Animal and Flying. We leave the vtable member as a void*

for now, since we will need these structures defined first:

struct Animal

{

void* vtable;

char* name;

};

struct Flying

{

void* vtable;

int32_t max_airspeed;

};

We can use these structures in the member functions to see better results in the decompiler:

int64_t Animal::greet(struct Animal* this)

{

_printf("You:\n");

_printf("Hello %s!\n", this->name);

_printf("%s:\n", this->name);

return *(int64_t*)this->vtable();

}

Tip

this is a keyword in the type parser, so if you try to define the function prototype with

this as the name of a parameter, you will get an error. You can enclose the parameter name

with backticks to work around this. Here, the parameter declaration would need to be

Animal* `this` to pass the type parser.

Defining the derived classes¶

The Dog, Cat, and Lion classes can be defined by using the derived structure feature, with the base class at offset zero. These classes

will look like this at this point:

struct __base(Animal, 0) Dog

{

__inherited void* Animal::vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

int32_t bark_count;

};

struct __base(Animal, 0) Cat

{

__inherited void* Animal::vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

int32_t nap_count;

};

struct __base(Cat, 0) Lion

{

__inherited void* Animal::vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

__inherited int32_t Cat::nap_count;

};

Applying these structures to the parameter types will improve decompilation of these classes:

void Dog::make_sound(struct Dog* this)

{

_puts("Woof!");

this->bark_count = (this->bark_count + 1);

}

void Cat::nap(struct Cat* this)

{

this->nap_count = (this->nap_count + 1);

}

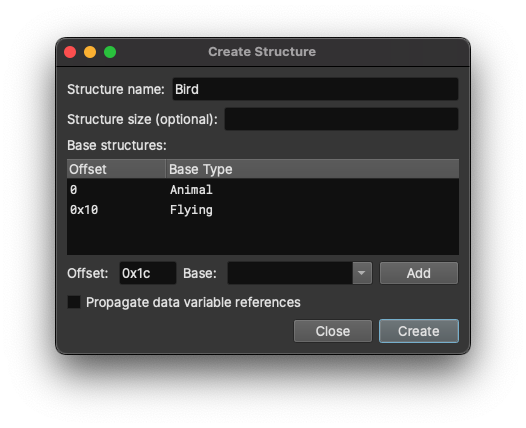

Multiple inheritance¶

The Bird class derives from both Animal and Flying. The typical in-memory layout of this

class is to place Animal at offset zero, Flying just after Animal, and any members from

the derived class after both. We set up this structure in the Create Structure dialog by first

adding Animal as a base structure and then adding Flying. The Create Structure dialog will

automatically adjust the offset as you add structures. The dialog should look like this after

the base structures are added:

After defining and adding the additional member, the Bird structure looks like this:

struct __base(Animal, 0) __base(Flying, 0x10) Bird

{

__inherited void* Animal::vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

__inherited void* Flying::vtable;

__inherited int32_t Flying::max_airspeed;

int32_t song_length;

};

Base class virtual function tables¶

Now it is time to start adding the virtual function tables, starting with the base classes.

Add the virtual function table structures for Animal and Flying. Ensure to check the

"propagate data variable references" option when creating any virtual function table. The

virtual function table structures will look like this:

struct __data_var_refs vtable_for_Animal

{

void (* make_sound)(struct Animal* this);

void (* approach)(struct Animal* this);

};

struct __data_var_refs vtable_for_Flying

{

void (* fly)(struct Flying* this);

};

Change the vtable members in the base classes to point to the virtual function table

structures:

struct Animal

{

struct vtable_for_Animal* vtable;

char* name;

};

struct Flying

{

struct vtable_for_Flying* vtable;

int32_t max_airspeed;

};

Now, go to the data section and apply the virtual function table structures to the virtual function tables themselves:

00004020 struct vtable_for_Animal _vtable_for_Animal =

00004020 {

00004020 void (* make_sound)(struct Animal* this) = nullptr

00004028 void (* approach)(struct Animal* this) = Animal::approach()

00004030 }

00004050 struct vtable_for_Flying _vtable_for_Flying =

00004050 {

00004050 void (* fly)(struct Flying* this) = Flying::fly

00004058 }

Derived class virtual function tables¶

The virtual function tables for the derived classes should be derived from the virtual

function tables for the base classes using the

derived structure feature. Define the

Dog and Cat virtual function tables with a base of vtable_for_Animal:

struct __base(vtable_for_Animal, 0) __data_var_refs vtable_for_Dog

{

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::make_sound)(struct Animal* this);

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::approach)(struct Animal* this);

};

struct __base(vtable_for_Animal, 0) __data_var_refs vtable_for_Cat

{

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::make_sound)(struct Animal* this);

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::approach)(struct Animal* this);

void (* nap)(struct Cat* this);

};

Define the Lion virtual function table with a base of vtable_for_Cat:

struct __base(vtable_for_Cat, 0) __data_var_refs vtable_for_Lion

{

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::make_sound)(struct Animal* this);

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::approach)(struct Animal* this);

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Cat::nap)(struct Cat* this);

};

Change the vtable inherited members in the derived classes to point to the correct

virtual function table structure for that class:

struct __base(Animal, 0) Dog

{

struct vtable_for_Dog* vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

int32_t bark_count;

};

struct __base(Animal, 0) Cat

{

struct vtable_for_Cat* vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

int32_t nap_count;

};

struct __base(Cat, 0) Lion

{

struct vtable_for_Lion* vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

__inherited int32_t Cat::nap_count;

};

Apply the new virtual function table structures to the virtual function tables in the data section:

00004078 struct vtable_for_Dog _vtable_for_Dog =

00004078 {

00004078 void (* make_sound)(struct Animal* this) = Dog::make_sound()

00004080 void (* approach)(struct Animal* this) = Animal::approach()

00004088 }

000040b0 struct vtable_for_Cat _vtable_for_Cat =

000040b0 {

000040b0 void (* make_sound)(struct Animal* this) = Cat::make_sound

000040b8 void (* approach)(struct Animal* this) = Cat::approach()

000040c0 void (* nap)(struct Cat* this) = Cat::nap()

000040c8 }

000040f0 struct vtable_for_Lion _vtable_for_Lion =

000040f0 {

000040f0 void (* make_sound)(struct Animal* this) = Lion::make_sound

000040f8 void (* approach)(struct Animal* this) = Cat::approach()

00004100 void (* nap)(struct Cat* this) = Cat::nap()

00004108 }

At this point virtual method calls in the decompilation should start looking more correct:

void Animal::greet(struct Animal* this)

{

_printf("You:\n");

_printf("Hello %s!\n", this->name);

_printf("%s:\n", this->name);

this->vtable->make_sound(this);

}

Virtual function tables with multiple inheritance¶

The Bird class is derived from both Animal and Flying, so it has two different virtual function

tables, one for each base class. Define both virtual function table structures, each deriving from

the base class that it came from:

struct __base(vtable_for_Animal, 0) __data_var_refs vtable_for_Bird_as_Animal

{

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::make_sound)(struct Animal* this);

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Animal::approach)(struct Animal* this);

};

struct __base(vtable_for_Flying, 0) __data_var_refs vtable_for_Bird_as_Flying

{

__inherited void (* vtable_for_Flying::fly)(struct Flying* this);

};

There were two inherited vtable members in the Bird structure. Replace the types of these with

the new derived virtual function table types:

struct __base(Animal, 0) __base(Flying, 0x10) Bird

{

struct vtable_for_Bird_as_Animal* animal_vtable;

__inherited char* Animal::name;

struct vtable_for_Bird_as_Flying* flying_vtable;

__inherited int32_t Flying::max_airspeed;

int32_t song_length;

};

Apply the virtual function table structures to the corresponding virtual function tables in the data section:

00004130 struct vtable_for_Bird_as_Animal _vtable_for_Bird_as_Animal =

00004130 {

00004130 void (* make_sound)(struct Animal* this) = Bird::make_sound()

00004138 void (* approach)(struct Animal* this) = Bird::approach()

00004140 }

00004150 struct vtable_for_Bird_as_Flying _vtable_for_Bird_as_Flying =

00004150 {

00004150 void (* fly)(struct Flying* this) = Flying::fly

00004158 }

Now the decompiler is able to determine the destination of a virtual function call in Bird:

void Bird::approach(struct Bird* this)

{

this->flying_vtable->fly(&this->flying_vtable);

}

The transformation on the this parameter is the compiler obtaining a pointer to Flying from

the Bird instance so that it can be used by the Flying class.

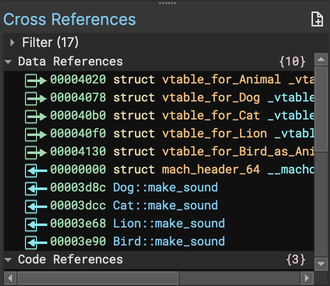

Cross references¶

Now that the data structures have been set up, Binary Ninja can provide helpful cross references

when navigating the C++ program. For example, clicking on the make_sound member in the Animal

structure will populate the cross references view with the list of functions that implement the

method:

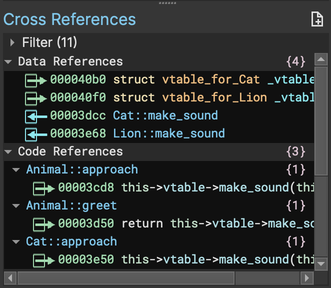

These cross references are aware of context when viewed from code. For example, in the following function:

void Cat::approach(struct Cat* this)

{

if (this->nap_count == 0)

{

this->vtable->make_sound();

}

else

{

_puts("Zzzz...");

}

}

Clicking on make_sound will populate the cross references with only the functions that are

in Cat or derived classes of Cat:

Offset Pointers¶

When implementing multiple inheritance, sometimes compilers will define a pointer to a class as

pointing into the middle of the memory layout of that class. If this is the case, you can use

the __ptr_offset attribute on a structure to tell Binary Ninja that pointers to the structure

are actually pointing at the given offset into the structure. For example, consider the following

definition:

struct __ptr_offset(4) Foo

{

int fizz;

int buzz;

};

When dereferencing Foo*, Binary Ninja will treat buzz as the member being pointed to, with

fizz being at offset -4.